Would Cleveland Officials Rather Have a Riot Than Justice?

Originally published on Ebony.

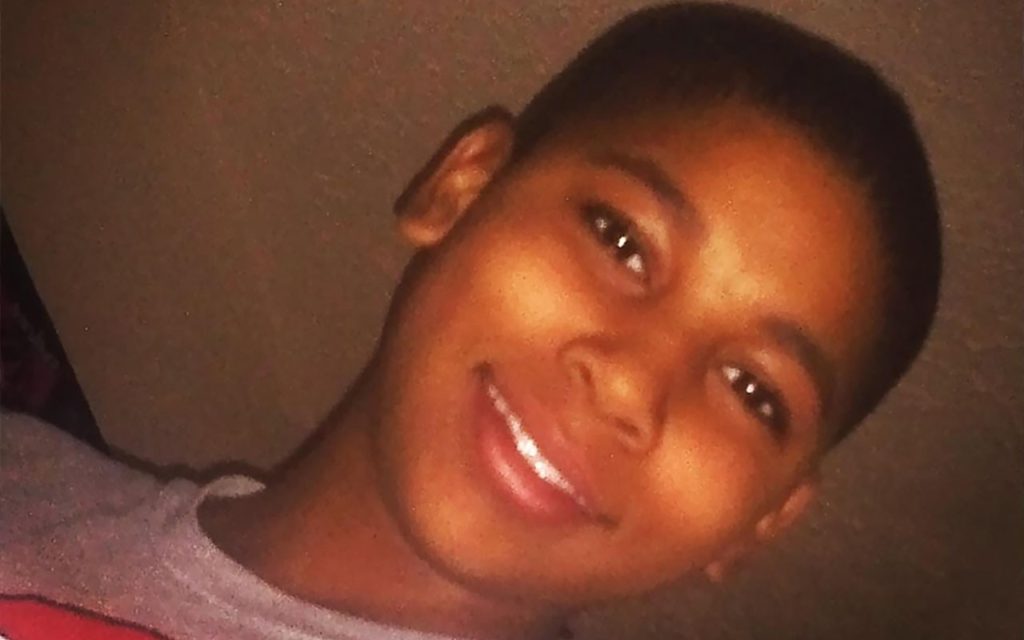

Two weeks ago today, I, along with seven other Cleveland area activists, filed affidavits with the municipal court calling for the arrest of Police Officers Timothy Loehmann and Frank Garmback for their involvement in the killing of 12 year-old Tamir Rice. Tamir was gunned down in less than two seconds in a park at a community center near his home. While many in the community have applauded our approach as a breath of fresh air toward obtaining justice, Police Patrolmen’s Association President Steve Loomis called it “vigilantism” and labeled us advocates of “mob rule.”

Last week, following Judge Ronald Adrine’s ruling that there is probable cause that Loehmann should face murder, reckless homicide, dereliction of duty and involuntary manslaughter charges (and Garmback should face charges for negligent homicide and dereliction of duty), we filed an action with the 8th District Court of Appeals to compel the judge to issue arrest warrants for the officers.

Many of our critics like Loomis, whose predecessor has called Tamir Rice’s killing by police “justifiable,” believe that we are trying to “hijack the rule of law and the constitutional process.”

But rather than evade the law, we are exercising our statutory rights as citizens of Ohio who believe there is enough probable cause a crime was committed. We believe that a secret grand jury process, solely controlled by the local prosecutor, would allow Officers Loehmann and Garmback to receive special treatment, just as the county prosecutor’s decision to not issue an arrest at any point over the last six months since Tamir’s killing has done.

This is the brand of justice that Loomis prefers for police: one that allows for police who kill unarmed citizens to circumvent the law. We have seen this already play out similarly across the country in other high profile cases since last summer—in Ferguson, MO (Mike Brown), Dayton, OH (John Crawford) and New York City (Eric Garner).

More specific than a general appeal to police accountability, which has become a catchall phrase in the contemporary movement to end police killings of unarmed Blacks, two core issues resonate in this fight. First, ending our society’s current practice in which police who commit crimes are allowed to operate above the law. And second, bridging the outlandish gap between this coddling of police officers and the harsh, unequal and sometimes illegal treatment of Blacks by the criminal justice system, often meted out by some of these same officers.

Because of these contradictions, many of this nation’s Black youth, including those who joined street protests in Ferguson and New York, Oakland, Los Angeles, Baltimore and other cities, have concluded that the criminal justice system is bankrupt. They have run out of patience with the labyrinth of legal loopholes from judges and prosecutors to grand juries and juries sympathetic to police that collapse over and over again to deem police innocent no matter how egregious the offense.

It is one of those ugly blemishes on our society, which prides itself on fairness, equality and transparency, where what has become common practice is out of synch with the democratic principles this nation claims to hold dear—in this case, a justice system that protects police from the rule of law at the expense of justice denied for citizens killed or violated when police make mistakes.

Across the country, almost routinely, police get away with murder. They hide behind the so-called blue wall of silence, are assumed always right, and police themselves. Out of thousands of on-duty police officer involved in fatal shootings of civilians over the last decade, only 54 officers have been charged, and most of those charged have been cleared or acquitted, according to a recent Bowling Green State University/Washington Post analysis.

A study of Cleveland police officer involved shootings by the Cleveland Plain Dealer found that police killed 32 suspects in 61 shootings between 2000 and 2014. All were deemed justified by prosecutors, grand juries, or the police.

In the days leading up to the police officer Michael Brelo verdict, Cleveland officials were unrelenting in their appeal to citizens to not riot. But they had little to say about justice for Malissa Williams and Timothy Russell, who were shot at 137 times by Cleveland police officers. Likewise, the demonstration of police force in the aftermath of the verdict raises the question, are officials better prepared to resist a riot protesting blatant injustice than they are willing to close the loopholes in a two-tiered system of justice that favors police?

This is not a veiled threat. It is an appeal to the reality that Williams and Russell deserved better. So does Tanisha Anderson, who died at the hands of a police officer using a takedown move. So does Tamir Rice. So do the citizens of this city. Signing these affidavits was our attempt to eke out a bit of justice from a bankrupt system in need of radical transformation. It is an opportunity for our city to re-imagine what justice looks like.