Not Your Grandmother's Women's Convention

Nine months after the Women’s March, a surprisingly diverse crowd of 5,000 met in Detroit for the inaugural Women’s Convention. Their mission? To transform the energy of the march into strategy, bridge gaps and build power.

When I arrived at 10 a.m. on Saturday (October 28), thousands of women from across the United States had already filled Detroit’s Cobo Center for the inaugural Women’s Convention, a followup to January’s historic Women’s March. From its inception this summer, the Convention was challenged—by lingering racial tensions from the march, criticism of the $295 cost of general admission and the scheduling of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), a man, as an opening-night speaker. (Sanders went to Hurricane Irma-ravaged Puerto Rico instead.) Under these conditions, could the Women’s March movement truly unite women across race and gender politics and help them build the power to defeat Trump’s MAGA agenda?

Surprisingly, the Convention crowd appeared to be equal parts White women and women of color, and there was a smattering of men in attendance, including me. Michelle Murguia, an 18-year-old college freshman from Albuquerque who works on deportation defense with New Mexico Dream Team, says the attendance defied her expectations. “I didn’t expect to see a lot of diversity here,” she told me in crowded hallway outside the main auditorium. ”It’s just amazing to see these strong women from diverse cultures fighting for their rights.”

Rana Abdelhamid, 24, founding president of The Women’s Initiative for Self-Empowerment, was also skeptical, but she made the trek from Palo Alto, California, anyway. “Being at the Women’s Convention was one of the most beautiful spaces I’ve ever been in as a woman of color. There was a sea of women of color and everyone was empowered to call out White feminism, White supremacy and White violence,” she said in a telephone interview the day after her presentation on self defense at the Convention. “I felt like I could speak my mind and speak my truth because it was such a diverse space. Also, the sessions were actively pushing well-intentioned White women to be better allies and accomplices in the fight for justice.”

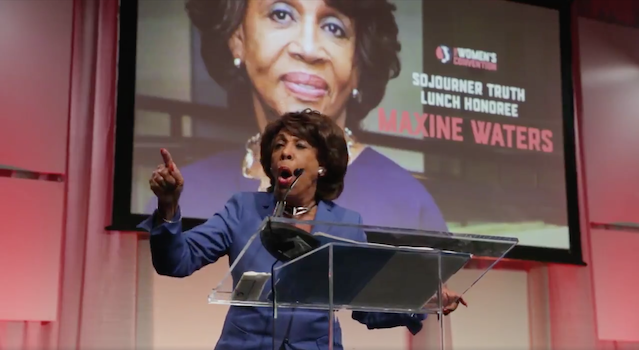

The diversity of the Convention was not a coincidence. The event borrowed its theme, “Reclaiming Our Time,” from Rep. Maxine Waters’ (D-Ca.) famous refrain and booked her as the conference keynote. And leaders of color in the Women’s March movement, including activists Linda Sarsour, Tamika Mallory and Carmen Perez, were highly visible on social and news media.

A cross-section of grassroots activists such as Rosa Clemente of #PRontheMap, Tarana Burke, #MeToo movement founder, and Shakyra Diaz, managing director of the Alliance for Safety and Justice, added to the diverse voices. They spoke bluntly about the past and current challenges of organizing women across vast race and class divides on issues from sexual assault to mass incarceration to the rebuilding of Puerto Rico.

At one of the most attended breakout sessions, “94 Percent Voted Against Trump: Black Women in 2018,” panelists including Melanie Campbell, CEO of the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation, and Brittney Packnett, cofounder of Campaign Zero, discussed Black women’s fight for resources and recognition while navigating slights by their White counterparts. Symone Sanders, who served as the national press secretary for Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign, moderated the session and Women’s March movement leader Mallory led off the question-and-answer period by asking the mostly Black crowd how they deal with the power dynamics of their emerging leadership. “We have been left on the sidelines so long that we have to think about what happened when we are invited in the room, and we show up hard, and sometimes make people run away. How do we deal with that?”

After the session, Mina* Davis, a 25-year-old debate coach from Omaha who is running for state legislature, called for the Democratic Party to be more inclusive of women of color. “I would like to see more involvement. I’m half Black and half Filipino. I am the only woman of color running in state legislature,” said Davis, who is also a member of the Nebraska Democratic Party. ”I’ve found that showing up is half the battle, but I think Democrats need to work harder to bring more people of color into the fold.”

But while some attendees were focused on the politics of the Democratic Party, many were focused on issues and activism that transcended electoral political concerns.

The breakout session “Confronting White Womanhood” was so popular on Friday that organizers repeated it on Saturday. That session easily had about 500 of mostly White participants. “How can you consider yourself a feminist if the only issue for you is gender equality?” Rhiannon Childs,** one of the session leaders and co-chair of the Women’s March Ohio chapter, asked the crowd. “It’s time to end White womanhood and rise up in sisterhood.” Her comments received a standing ovation.

The Convention also served as a social gathering space. Throughout the day, women gathered in the atrium to take photos in front of a vibrant social justice art exhibit. Some made new friends. Others had come with old friends such as Abdelhamid. She came with Dami Oyefeso, a Queens, New York, publicist whom she met years ago in the Posse Foundation’s scholars program.

By chance, Pamela Perry, a 61-year-old Army veteran and retiree from the human services sector, reconnected with 18-year-old Khadega Mohammed, a Sudanese immigrant from Saudi Arabia whom she met a year earlier on a Greyhound bus from Chicago.

Mohammed, a Detroit-area college student and spoken-word poet, encountered Convention organizer Sarsour, whom she met last year at one of her performances. But she said that beyond the camaraderie she didn’t get much out of the convention. “It was a cool environment to be in, but I felt not enough emphasis was placed on what we can take away to continue protesting and marching,” she told me.

Perry, who attended the Women’s March on Washington, said she had been concerned about the lack of African-American women organizing the marches when she joined the Illinois planning committee. But at the Convention, she was excited to meet people such as 60-year-old Remi Ogidan, whom she encountered on an Amtrak train and discovered that they were both headed to the Convention. “As we talk about bringing women together to rally around issues that impact us, we have to be concerned about what we are for, not just what we are against,” she told me. ”African-American women need to reach across the aisle, not only to White women but also to women who voted for Trump.”

The Convention also served as a social gathering space. Throughout the day, women gathered in the atrium to take photos in front of a vibrant social justice art exhibit. Some made new friends. Others had come with old friends such as Abdelhamid. She came with Dami Oyefeso, a Queens, New York, publicist whom she met years ago in the Posse Foundation’s scholars program.

By chance, Pamela Perry, a 61-year-old Army veteran and retiree from the human services sector, reconnected with 18-year-old Khadega Mohammed, a Sudanese immigrant from Saudi Arabia whom she met a year earlier on a Greyhound bus from Chicago.

Mohammed, a Detroit-area college student and spoken-word poet, encountered Convention organizer Sarsour, whom she met last year at one of her performances. But she said that beyond the camaraderie she didn’t get much out of the convention. “It was a cool environment to be in, but I felt not enough emphasis was placed on what we can take away to continue protesting and marching,” she told me.

Perry, who attended the Women’s March on Washington, said she had been concerned about the lack of African-American women organizing the marches when she joined the Illinois planning committee. But at the Convention, she was excited to meet people such as 60-year-old Remi Ogidan, whom she encountered on an Amtrak train and discovered that they were both headed to the Convention. “As we talk about bringing women together to rally around issues that impact us, we have to be concerned about what we are for, not just what we are against,” she told me. ”African-American women need to reach across the aisle, not only to White women but also to women who voted for Trump.”

The Convention also served as a social gathering space. Throughout the day, women gathered in the atrium to take photos in front of a vibrant social justice art exhibit. Some made new friends. Others had come with old friends such as Abdelhamid. She came with Dami Oyefeso, a Queens, New York, publicist whom she met years ago in the Posse Foundation’s scholars program.

By chance, Pamela Perry, a 61-year-old Army veteran and retiree from the human services sector, reconnected with 18-year-old Khadega Mohammed, a Sudanese immigrant from Saudi Arabia whom she met a year earlier on a Greyhound bus from Chicago.

Mohammed, a Detroit-area college student and spoken-word poet, encountered Convention organizer Sarsour, whom she met last year at one of her performances. But she said that beyond the camaraderie she didn’t get much out of the convention. “It was a cool environment to be in, but I felt not enough emphasis was placed on what we can take away to continue protesting and marching,” she told me.

Perry, who attended the Women’s March on Washington, said she had been concerned about the lack of African-American women organizing the marches when she joined the Illinois planning committee. But at the Convention, she was excited to meet people such as 60-year-old Remi Ogidan, whom she encountered on an Amtrak train and discovered that they were both headed to the Convention. “As we talk about bringing women together to rally around issues that impact us, we have to be concerned about what we are for, not just what we are against,” she told me. ”African-American women need to reach across the aisle, not only to White women but also to women who voted for Trump.”

Standing in line at Hall D around 1:30, it was clear that, despite some differences, attendees were united in their excitement about hearing Waters address the convention. Emceed by image activist and creative director Michaela angela Davis and “Newsone Now” anchor Roland Martin, the “working lunch” that honored Waters was peppered with shout-outs to Sojourner Truth, Grace Lee Boggs and Rosa Parks.

In her 20-minute speech, Waters shouted out some of her Democratic congressional colleagues, including Reps. John Conyers (D-Mi.) and Frederica Wilson (D-Fl.) but focused on the core concerns of progressive, poor and middle class Democrats.

“We are speaking to women who are single mothers, women who are working two or three jobs making minimum wage or less, women who have been exploited and harassed or taken advantage of in their personal or professional lives, women who are suffering from illness and diseases who are worried about the future of healthcare, women who have been disrespected in the boardroom or feel that their talent is not appreciated or valued in the work place,” she said. “Today we are gathered to discuss the issues and organize a plan of action to continue our resistance.” And, of course, she led the crowd in a round of “Impeach 45” chants.

Dami Oyefeso, a Queens, New York, publicist who is registered as an Independent, said that while she found Waters’ speech inspiring, she had come to see how the Convention would defy stereotypes of White feminism. “I had never been to a women’s convention, and I wondered how the march that was so huge could be turned into dialogue and not just one-way activism but a conversation between ourselves,” said Oyefeso. ”Feminism has this bloated history of not being inclusive. I was interested in seeing how the Women’s Convention would stack up. They did really well in terms of the inclusiveness of trans women, women of color, hijabi and non-hijabi Muslims, and everyone that identifies as a woman.”

At the end of the day, it was clear to me that the Women’s Convention—the first of its kind in 40 years—filled a void. What remains to be seen is whether the gathering will help channel the vast concerns of ordinary women into a force that can transform the landscape of mainstream American politics.